For research assistance, please contact University Archives and Special Collections at library.archives@umb.edu.

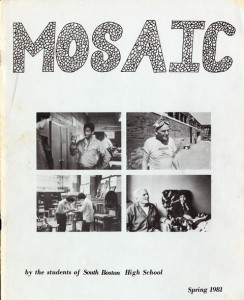

Spring 1981 issue of Mosaic, a publication by the students of South Boston High School. Image Source: SC-0045 Mosaic Records, 1980-1990.

The University of Massachusetts Boston's University Archives and Special Collections has many resources that expound the controversy that surrounded the school desegregation movement in Boston. The citywide crisis was ignited with Judge Arthur Garrity's ruling in the case of Tallulah Morgan et al. v. James Hennigan et al. in 1974 where Garrity ruled that the Boston School Committee had purposefully maintained racial segregation in Boston Public Schools. Judge Garrity went on to implement a plan that bused students to various schools to achieve racial balance.

School desegregation became a significant issue after the United States Supreme Court decision in the 1954 case of Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka et al. The Brown decision espoused that separate educational facilities for black and white students were inherently unequal and public schools must be integrated. However, Boston Public Schools remained unbalanced in the 1970s despite the Brown decision and the enactment of the Racial Balance Act of 1965.

Because of this inaction, on March 15, 1972, a group of Black parents filed suit against the Boston School Committee led by James W. Hennigan, in the case of Tallulah Morgan et al. v. James Hennigan et al, which claimed that the Boston Public Schools were deliberately kept segregated. On September 21, 1971, the Boston School Committee met and voted against using busing as a method to racially balance a new school opening in Boston, a clear violation of the Racial Imbalance Act of 1965, and sparked the lawsuit.

On June 21, 1974, Judge Arthur W. Garrity ruled in favor of the plaintiffs and ordered the Boston School Committee to submit a plan to desegregate the public schools. Garrity began to enforce the State Board of Education's plan for reducing racial imbalance that dictated that the "racial balance in all citywide schools shall be reflective of the total student population in the Boston Public School system." This became known as Phase I of Garrity's plan and began on September 12, 1974, the first day of the school year. The plan involved redistricting, student transportation, and the formation of parent committees. This phase affected only the neighborhoods in which black and whites lived near each other and therefore Charlestown, East Boston, and the North End were excluded for this first phase.

Phase II began in September 1975 and included all areas of Boston, except East Boston. Also referred to as "The Master's Plan," this phase required the revision of attendance zones and grade structures as well as the construction of new schools, and a controlled transfer policy. Students could either attend a school in their community district schools where the enrollment was determined by the school committee or attend a citywide school where they could list a preferred schools in order of preference. This phase also linked local universities, colleges, and community groups to the schools.

In September 1977, Phase III began and established the Department of Implementation which oversaw desegregation and the compiling of racial statistics of the Boston Public Schools.

As the plan continued despite strong opposition in the 1970s, students and parents gradually accepted forced busing and racial tensions eventually lessened. Judge Garrity continued to oversee much of the administrative functions of the Boston School Committee and to make decisions regarding schooling and desegregation. Although Garrity's involvement ended in September 1985, the battle over schools and race continued in the federal courts into the 1990s.

Research guide created by Corinne Zaczek Bermon, Archives Assistant, August 2016.